Since 2011, Tunisia has turned into a final destination for new and diverse groups of refugees, including from Syria. Syrian refugees’ family networks, together with changing Arab border regimes, economic opportunities, and dreams of better lives, shape non-linear displacement trajectories to Tunisia.

“We came to Gafsa because where else would we go?” In early December 2021, Um Karim[1], a Syrian grandmother, explained to us how several generations of her extended family had ended up in a remote mining town in southwest Tunisia. In Jughurta, a working-class neighbourhood on the outskirts of Gafsa, Um Karim and her husband, and various adult sons, daughters-in-law, and other relatives, all live in the same street. The story of how Um Karim moved from Homs, her natal city, to Gafsa, is not straightforward. Before the Syrian conflict, her husband, Abu Karim, worked as a trader, and frequently travelled to Jordan. Their more recent displacement, however, spans the entire southern Mediterranean. It includes multiple border crossings and an unlikely specific connection between two neighbourhoods more than 2,500 km away from each other: Karam al-Zeytoun, Homs, and Jughurta, Gafsa.

Syrian refugees make up around one quarter of Tunisia’s registered refugee population.[2] In recent years, Tunisia, long a migrant-sending country, has also become a transit region, and, at times, a final destination, for diverse groups of refugees and migrants.[3] It is a signatory of the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol, obliging it not to return refugees to countries where they might face serious threats to their life or freedom. Tunisia’s 2014 and 2022 Constitutions equally recognise the right to political asylum, but the country has yet to adopt its own domestic asylum legislation. For now, UNHCR, together with the Conseil Tunisien pour les Réfugiés, is responsible for the registration of asylum seekers and Refugee Status Determination.

We need to understand better the factors that shape refugees’ decision-making: how do refugees choose where to go? Can displacement combine multiple trips and migratory projects in different countries? In this article, we retrace the steps of Um Karim, and some of her Syrian relatives now living in Gafsa and Sousse, to demonstrate how family networks, together with border closures, economic opportunities, and dreams of better lives, shape non-linear displacement trajectories. Our findings show that many Syrian refugees follow their relatives’ well-trodden paths, and settle in kinship clusters in the host country. Their overreliance on family networks may trap them in remote places, where they have to survive with little or no humanitarian assistance.[4]

“My father brought us here”

In her living room in a sparsely furnished apartment, Um Karim, in her late 60s, towered over several generations of her offspring. While an old television in the corner quietly played her favourite religious talk show, she dominated the discussion, with occasional interjections from a middle-aged daughter-in-law, and the mother of one her younger sons’ brides. Although younger and older generations did not always agree on dates and details, we managed to piece together how Abu Karim’s decision to leave Homs in 2011 had led to the relocation of their entire extended family to Tunisia.

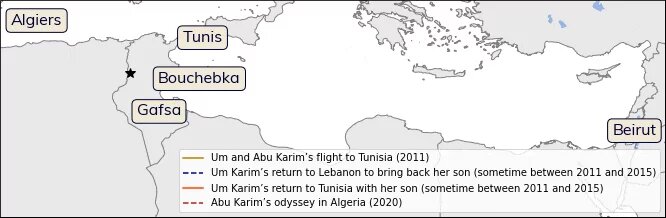

Map 1 shows the version of the grandparents’ meanderings that family members present in Um Karim’s living room could agree on. In 2011, in the early days of the Syrian conflict, Abu and Um Karim, one of their sons and his wife, boarded a flight from Damascus to Algiers. They only spent two days in Algeria, before travelling overland to Tunisia – at the time, Syrians could enter both countries without a visa. Gafsa was not a random choice. One of the couple’s daughters had arrived two months earlier, and Abu Karim also had other relatives in the Maghreb. In Gafsa, they duly reported to local authorities. Only four years later, the grandparents also registered with the UNHCR. Soon, Um Karim returned to the Middle East to reunite with one of her other sons, Ahmed. When the family had abandoned their house in Homs, Ahmed had left his passport behind. The home was later looted by strangers. Unable to travel without his papers, Ahmed stayed behind with a paternal uncle in Lebanon. Um Karim flew from Tunis to Beirut, bringing with her the Syrian family book proving Ahmed’s identity. In Lebanon, it took Um Karim and Ahmed one year to complete the paperwork. Finally, mother and son were able to return to Algiers together, this time from Beirut, from where they made their way to Gafsa.

Over the following years, more family members arrived to Gafsa: while some spent several years in informal camps in Lebanon, and later in rental housing in Algeria, others traversed both countries in only a few days. As another adult son, who had joined his parents in 2015 together with his wife, explained: “[My father] brought us here.” All of them entered Tunisia through the same border crossing: Bouchebka, close to Kasserine, in a frontier area known for intense smuggling activities and cross-border family ties.[5] In later years, they continued to use their knowledge of Tunisia’s border area for return trips to Algeria. Between 2019 and 2021, several family members travelled from Gafsa to Algiers to renew their passports at the Syrian embassy.[6] In early 2020, “at a time when there was a lot of snow”, the elderly Abu Karim himself got lost in Algeria. On the road, his papers were stolen and he was arrested by Algerian police. According to Abu Karim, his passport carried an older Algerian entry stamp, and police would not allow him to return to Tunisia. Instead, they deported him to the desert between Algeria and Niger, together with another Syrian family. Abu Karim, a man in his seventies, walked hundreds of kilometres, surviving on food and water from local people. For two weeks, his family did not know what had become of him, until they heard that he had reached the Tunisian border.[7]

As map 1 illustrates, the family’s movements crisscross a world with hardening borders. As Um Karim put it: “Now the whole world is closed to us, you need a visa to go anywhere”. With rising unemployment and living expenses, life in Gafsa has turned into a dead end. Um Karim’s family is also aware of the high costs and risks involved with using smugglers to reach Europe or other Arab countries like Morocco. Even though very few refugees are officially resettled to the Global North from Tunisia every year[8], the family hope to reunite with daughters and granddaughters in Belgium and France. But not all of Um Karim’s dreams of mobility are related to no longer being a refugee. One of her other daughters lives in Saudi Arabia, and Um Karim would like to visit her to do the umrah, the Islamic pilgrimage.

“A different kind of fear”

Um Khaled, one of Um Karim’s daughters, has settled with her husband and teenage children in Sousse, a coastal city a five hours’ drive away from Gafsa. Map 2 follows their journey from Lebanon to West Africa and finally Sousse. The family’s repeated attempts at rebuilding their lives in exile show that kinship connections are only one factor among others that motivate refugees to keep moving. Host countries’ changing border regimes also reroute refugees’ travel plans, and members of the same family might reach the same destination through different channels. Um Khaled’s story is a case in point: unlike her parents and siblings, who were able to fly directly from the Middle East to Algeria, Um Khaled’s family travelled after Algeria had ended visa-free entry for Syrians in March 2015.[9]

When Abu Khaled, a pastry chef, his wife and four children left Syria in 2014, they first joined relatives in Egypt: from Beirut, they flew to Cairo, and spent eleven months in the nearby oasis of Fayoum. After their return to Lebanon, the family lived for another two years in an informal refugee camp close to Tripoli. When UNHCR cut their financial assistance, and locals burnt down the camp, they decided it was time to move again. A friend had told Abu Khaled that they could smuggle themselves back to Egypt via the Sudanese border. In October 2016, the family boarded a flight from Beirut to Khartoum, but their plan did not work out. Instead, Um Khaled’s uncle, a Syrian dentist based in Mauritania, bought the family plane tickets to Nouakchott and rented a house for them. In spring 2017, the family approached a Mauritanian smuggler who had been recommended by Syrian acquaintances. During a weeklong road trip, they crossed the Sahara on the back of a pick-up, together with two other Syrian families; Um Khaled counted a total of 26 passengers, among them ten children. At night, the adults made a camp in the desert and stood guard over their sleeping children. After the horrors of the Syrian conflict, Um Khaled described sleeping in the desert as “a new kind of fear”: the experience brought back memories of the kidnapping of women and children in Syria. In Al Khalil, a famous migration hub on the border between Mali and Algeria, the group changed cars and drivers. The new drivers did not speak any Arabic, leaving their passengers unable to communicate with them. A day later, they stopped in a desert village in Algeria; there, the families spent the night in one large room. In the morning, the group left for Tamanrasset, a transportation hub in southern Algeria, where they split up. Abu Khaled’s family first took a bus to Boudouaou, a town half an hour’s drive east of Algiers. In a local inn, one of his daughters gave birth. After twenty days, the family moved further east to the city of Bordj Bou Arreridj. They stayed for a year and a half and registered with UNHCR. Abu Khaled found work in a pastry shop, but rumours of more generous UNHCR assistance in Tunisia motivated them to move once more. And that’s when their paths converged again with their relatives in Gafsa.

In mid-2018, the family entered Tunisia through the Bouchebka border crossing. Algerian guards bought them sandwiches, and Tunisian officers paid for their onward fare. In Kasserine, the family was briefly stopped by police and registered, before they made their way to Um Karim’s house in Gafsa. After four months, Abu Khaled’s family moved to Sousse. Three years later, he was informed that he would have to appear in court for “illegally crossing the border”, but the case is still pending. Unlike the relatives we interviewed in Gafsa, Abu Khaled had not moved his family to Tunisia to follow in the footsteps of his father-in-law, Abu Karim. But Abu Karim’s house was their first destination in the new country, and years later, Abu Khaled’s 17-year old daughter was briefly married to a similarly young cousin in Gafsa. In September 2020, Abu Khaled’s family crossed the Tunisian-Algerian border once again: this time, to renew their passports at the Syrian embassy in Algiers. Due to Covid-19, the border was now closed[10], and he paid a Tunisian and an Algerian smuggler 75 TND (approx. 25 USD) per person. His daughter proudly showed us the renewal stamps in their passports: October 2021. Even at a time of pandemic-related border closures, Syrian cross-border movements thus continue – and families are still moving together.

Invisible refugees?

In our interviews with international and Tunisian aid providers, and representatives of several Tunisian municipalities, we learned that most stakeholders seemed to agree on one thing: unlike Sub-Saharan African migrants and refugees, Syrian refugees in Tunisia can integrate more easily thanks to their shared language, culture, and religious beliefs. The displacement stories we presented above also indicate that at least until the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Syrian refugees experienced the Algerian-Tunisian land border as porous, and Tunisian border guards as welcoming. However, Syrians’ ability to “blend in” is a double-edged sword: following family members, some have settled in deprived southern and interior areas, with few civil society support and limited job opportunities. In present-day Gafsa, only Um and Abu Karim, and other elderly or chronically ill family members, receive financial assistance from UNHCR. Rents are cheaper in Gafsa than in big cities like Tunis and Sousse, and that is what keeps the family there. At the same time, the lack of access to the formal labour market traps them in protracted poverty.[11] Um Karim’s sons and grandsons work as waiters and day labourers, getting paid around 30 TND (approx. 10 USD) a day. Her granddaughters sometimes find jobs as cleaners inside their neighbours’ houses. While some Syrians in big Tunisian cities have successfully established restaurants, refugees in deprived areas lack access to start-up grants that would allow them to open their own business. Precarious livelihoods go hand in hand with legal limbo. Many years after their arrival, Um Karim’s family have still not received official refugee status. As one son bitterly complained: “Will I spend fifteen years as an asylum-seeker in Tunisia?”

Dr Ann-Christin Zuntz’ research was funded by an IFG II Fellowship “Inequality and Mobility” at the Merian Centre for Advanced Studies in the Maghreb, Tunis.

[1] Between October and December 2021, we conducted interviews with 21 Syrian households in Tunisia, as well as key stakeholders in Tunisia’s refugee response. To protect Syrian interviewees, all names have been changed.

[2] UNHCR (2022), “Refugees and asylum-seekers in Tunisia”, https://data2.unhcr.org/en/country/tun, accessed 21 April 2022.

[3] Garelli, Glenda, and Martina Tazzioli (2017), Tunisia as a Revolutionized Space of Migration, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

[4] For a more extended discussion of Syrian refugees’ flight trajectories, see our policy brief Zuntz, Ann-Christin et al. (2022), “Destination North Africa - Syrians' displacement trajectories to Tunisia”, https://mixedmigration.org/resource/destination-north-africa/.

[5] Miller, Alyssa (2018), Shadow Zones: Contraband and Social Contract in the Borderlands of Tunisia, Doctoral thesis, Duke University.

[6] Since 2011, the Syrian embassy in Tunis has been closed. As our interview findings indicate, Syrians in Tunisia need valid passports to retrieve remittances; some also want to feel prepared for onward travel, be it for resettlement to the Global North, or to return to Syria.

[7] Abu Karim’s story is corroborated by reports from human rights organisations, for example Human Rights Watch (2020), “Algeria: Migrants, Asylum Seekers Forced Out”, 9 Oct, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/10/09/algeria-migrants-asylum-seekers-forced-out.

[8] UNHCR (2021), “UNHCR Tunisia Operational Update - December 2021”, https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/90564.

[9] Reach and Mixed Migration Centre (2018), “From Syria to Spain: Syrian Migration to Europe via the Western Mediterranean Route”, https://mixedmigration.org/resource/from-syria-to-spain/.

[10] Infos Algerie (2022), “Réouverture des frontières terrestres entre l’Algérie et la Tunisie, Infos Algerie”, 5th Jan, https://infos-algerie.com/2022/01/05/voyage/reouverture-frontieres-terrestres-algerie-tunisie/.

[11] Displaced people registered with UNHCR as “asylum-seekers” or “refugees” do not automatically receive residency and work permits.