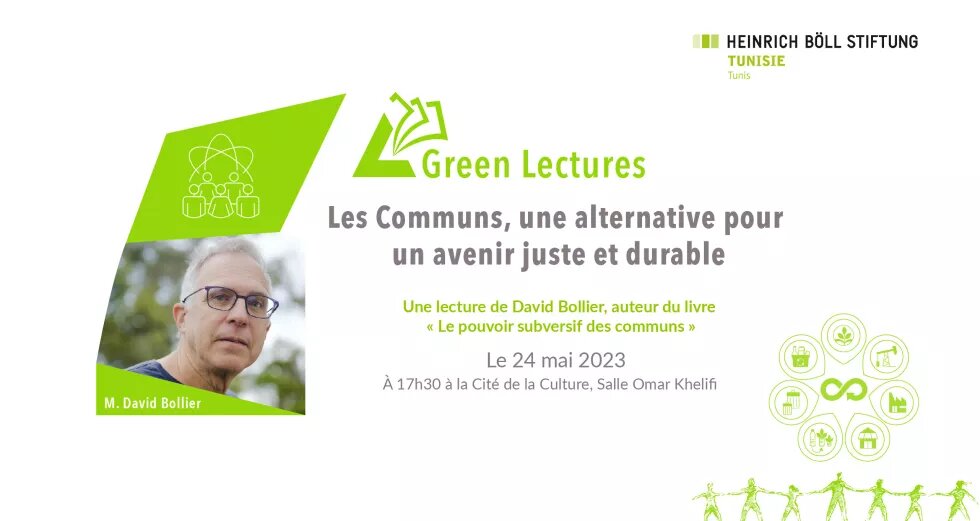

On May 24, 2023, Green Lecture #6 in Tunis highlighted the "Commons with David Bollier. A promising concept for a sustainable society. Discover the event and the live video!

On May 24, 2023, the Cité de la Culture in Tunis buzzed with excitement as it hosted the sixth edition of the Green Lecture, an event organized by the office of the Heinrich Böll Foundation Tunis. This year's conference highlighted an emerging concept: the "Commons," with the presence of David Bollier, co-author of "Free Fair and Alive." This encounter offered a unique opportunity for Tunisians to acquaint themselves with this innovative concept that has garnered significant interest within the global intellectual community.

But what exactly are the Commons? The concept proposes a collective, equitable, and sustainable management of resources, whether material or immaterial. Although the term may sound new, the "Commons" have ancient roots in Tunisia, where resource-sharing practices were commonplace in the past. Tunisian farmers, for instance, would gather around a water source to meet their daily needs or cultivate their gardens and oases. Today, this concept takes on a new dimension, providing a pertinent approach to addressing ecological, social, and economic crises humanity faces and to building resilient and sustainable societies.

The Green Lecture was an opportunity to rediscover the concept of the "Commons" in Tunisia and foster constructive dialogue based on concrete examples drawn from local practices related to this notion. Speakers shared the various vibrant forms of "Commons" present in Tunisian society, practices that have endured throughout history up to the present day. The objective of this event was to raise awareness among the public about the ideas and practices associated with the "Commons," highlighting their benefits and the challenges they pose for governing shared resources in Tunisia.

The panel for this conference comprised two distinguished experts in the field. Firstly, David Bollier, co-author of "Free Fair and Alive," took the stage to introduce the conference and share his expertise on the subject. Subsequently, Safouane Azzouzi, a Tunisian researcher specialising in the field of "Commons," shed light on local practices and their relevance within the Tunisian context.

This conference showcased that the "Commons" represent a promising path towards constructing a fairer and more sustainable future. By emphasizing collective and equitable resource management, this concept provides a robust alternative to traditional models, fostering cooperation and solidarity within society. The concrete examples presented during the event demonstrated that the "Commons" aren't merely abstract concepts but are deeply rooted in Tunisian history and culture.

Beyond exploring the "Commons" concept, this Green Lecture also offered participants the opportunity to discover the content and platform "Commons Library" developed by the office of the Heinrich Böll Foundation in Tunis.

Green Lecture #6 on the "Commons" was a success, affording Tunisians a unique opportunity to become informed, debate, and reflect on this alternative approach for shaping a more enduring and resilient future. By exploring local practices and benefiting from the expertise of individuals like David Bollier and Safouane Azzouzi, the audience is left with an enhanced understanding of this promising concept and its prospects for a fairer and more responsible society regarding shared resources.

For those who were unable to attend the event, the live video of the conference is now available on the official page of the Heinrich Böll Foundation Tunis. Here is the link to the video:

Et ci-dessous, vous trouverez le texte de la présentation intégrale de David Bollier traduit en français.

The Commons as Islands of Shared Purpose and Provisioning

The Green Lecture by David Bollier at Heinrich Boell Foundation-Tunis

Tunis, Tunisia / May 24, 2023

Thank you for your generous invitation to offer this Green Lecture to you today.

Reflecting on the Boell Foundation's work, this audience and my own experiences as a commons scholar and activist, I came to realize that we share many sensibilities. I was tempted to entitle my talk, "The Unsuspected Power of Underdogs and How They Prevail." We are each in our different ways struggling to overcome the economic, social, and ideological wreckage of the 20th Century, which feels like a deadweight around our necks. How can we emancipate ourselves from some archaic ideas and ineffective institutions, and move forward with fresh ideas and institutions that take account of our actual realities?

Today, I'd like to introduce the idea of the commons to you and suggest its enormous potential for re-imagining so many things – the political economy, our social relations, our relations with the Earth, our inner lives. To be sure, this is a difficult proposition. We not only have to develop some very different social logics and institutional forms while immersed in an entrenched and hostile legacy system. We also have to change ourselves. We each in our different ways, whether from the North or South, cities or countryside, or different racial or religious backgrounds, have to overcome the many unresolved traumas of capitalism, colonialism, and centralized state power whose norms we have internalized or repressed.

I am so pleased that my book – Free, Fair and Alive, coauthored with my late colleague Silke Helfrich – is finally published in French, as Le Pouvoir Subversif des Communs! I'm excited because our book grapples with many of the very issues I just mentioned. It distills the lessons of Silke's and my extensive fieldwork studying dozens of commons around the world, and our study of capitalist modernity and politics. We concluded that the commons – truly one of the great underdog concepts of our time! – has a brighter future than respectable opinion can fathom.

Respectable opinion continues to believe that the market and state are the only consequential systems for getting stuff done. (I like to call it the market/state because of the deep symbiotic alliance between market and state and their shared vision of economic growth, progress, rationality, and separations of humanity from nature, mind from body, and individual from the collective.) But given the deepening crisis of climate change and other ecological catastrophes, given the myriad harms and alienation caused by wealth inequality and precarity and capitalist structures, I believe the commons -- in cooperation with other system-change movements – may be one of the few practical escape routes available to us

Why this confidence? you may ask. Because the human impulse to common is timeless. It's instinctual. Our ability to cooperate and share – to devise collective rules, to negotiate differences, to uphold community coherence in the face of free-riders and vandals – is as old as the human species itself. Evolutionary scientists will tell you that cooperative strategies are a primary reason why human beings have survived for millennia. Commoning is how we humans developed tools and agriculture, religion and art, and language and culture. Commoning – speaking from an historical, civilizational perspective – is our species' default system of governance. The libertarian, individualistic extremes of industrial and contemporary digital capitalism -- and of the modern nation-state – are bizarre aberrations in the long sweep of human history.

So the commons is not a new thing; it's an ancient thing. And it's not a Western idea (even if the West is now rediscovering it). The commons is a universal social form – or perhaps more fundamentally, an attribute of living systems. Life itself arises through symbiotic relationships and deep interdependencies, as ecosystems and cul as Gaia demonstrate.

Another reason why I am so optimistic about the future of the commons is the actual diversity and power of countless commons right now. There is a huge universe of bottom-up commoning initiatives flourishing around the world. The problem is that these projects, while pervasive, are microly invisible.

Still, millions of people are engaged in commoning because it's a way to meet their needs and enhance their security through direct, self-organized provisioning and governance. Instead of looking to the state, international bodies, and corporations – which themselves are often failing and falling apart – people are relying on commoning to grow their own food…. provide mutual aid to each other…. build housing…. safeguard water….and manage urban spaces. People are building digital commons for information and creative works….and developing software platforms to benefit users and the general public, and not just investors. They are devising alternative finance and money systems….providing care to the elderly, sick, and children…..and taking responsibility for many other everyday needs.

The general aim of any commons is to share or mutualize the benefits of collectively managed wealth. People who become commoners reject the idea of becoming private entrepreneurs or capitalists because they know what extractivist business strategies often entail: the exploitation of people, ecological destruction, political polarization, social instability. Commoners realize that the Invisible Hand won't take care of the common good. Nor will nation-states, who are so often beholden to capitalist investors and corporations. Commoners must themselves pioneer a new version of common good, at the cellular level of society, through their commons.

I must add that commons are systems that we choose ourselves. They don't rely on coerced "cooperation," whether from the state or market. The state may offer support to commons, and businesses may have limited forms of exchange with them. But outsider control or interference will destroy a commons. A critical attribute of any commons is therefore its autonomy. Participants must have the individual rights and freedoms to enter into community agreements, to freely assume responsibilities, and to benefit from the fruits of their cooperation.

And all of this must be done in a spirit of inclusion, not exclusion. Of course, commoners who take responsibility for work must have first claims on what is produced or stewarded. But having said that, commons strive to respect the dignity and needs of everyone regardless of gender, race, ethnicity, age, or religion. They are also mindful of the legacy of our ancestors and the needs of our children and future generations.

I hope you can sense why I think the commons might have some practical and inspirational value in Tunisia today. We live in an interregnum. The old order has not yet passed away but the new is not ready to be born. This means that there are rare openings in The System that can be exploited; there are special opportunities to innovate. The latent possibilities are available not only in countries like Tunisia, but places where people wish to move beyond conventional capitalist narratives of "development" and "progress."

You may wonder, What exactly does the concept of the commons imply that we should do – and how? In answer, I will first explain how standard economics and even many traditional commons scholars misconstrue the commons as resources, when in fact they are better understood as social systems. To illustrate this fact, I will offer a brief tour of the Commonsverse – the many projects, websites, movements, and books that comprise the world of the commons – so you can get a sense of just how vast and varied contemporary commons actually are. And finally, we must consider politics and law. How might the Commonsverse develop itself and engage constructively with conventional markets and state power?

* * *

For more than forty years, much of the educated public has considered the commons to be a failed management regime. This idea can be traced to a famous essay written by biologist Garrett Hardin in 1968, “The Tragedy of the Commons." Hardin presented a parable of a shared pasture on which no single herder has a “rational” incentive to limit his cattle’s grazing. The inevitable result, said Hardin, is that each person will selfishly use as much of the common resource as possible, which will inevitably result in its overuse and ruin – the so-called “tragedy of the commons.” The best solution, Hardin argued, is to allocate private property rights to resources – or use government coercion to regulate economic activity.

But here is the surprising thing: Hardin was not describing a commons. He was describing an open access regime or free-for-all in which everything is free for the taking. In an actual commons, as a social system, by contrast, there is a distinct community that governs the resource and its usage. Commoners negotiate their own rules of access and use, assign responsibilities and entitlements, and set up monitoring systems to identify and penalize free riders.

Professor Elinor Ostrom helped rescue the commons from the smear of the "tragedy" parable by documenting how hundreds of commons, mostly in rural settings in poorer nations, have in fact managed land and water and forests and fisheries sustainably. As an empirical matter, the commons can work, and work well. Ostrom’s landmark 1990 book, Governing the Commons, is justly renowned for identifying eight key “design principles” for successful commons. For her work, Ostrom won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2009, the first woman to be so honored.

Unfortunately, the economics profession and even Hardin and Ostrom have treated commons mostly as a matter of rational individuals using conventional property rights to manage resources, with relatively little attention to the social dynamics of commons. In our book Free, Fair and Alive, Silke Helfrich and I reverse the framing usually given to commons. We foreground the social dynamics of the commons as the main story -- and consider resources a subordinate issue. While the character of a resource can matter a great deal in a commons – some resources like land are finite and depletable; others, like software code, are easily reproduced and shared at little cost – the point is that there is no inherent logic in resources dictating how they must be allocated, used, and managed. That's a social choice. Societies decide that for themselves – or more accurately, the elite guardians of the state, capital, and law tend to impose their own priorities.

The point that must be stressed is that a commons is really about commoning – the commons as a verb, not a noun. Commons are a dynamic, evolving social practice, not as a thing or asset or resource. Of course, there are resources in commons, but what matters is that a defined community is applying its own self-devised rules, practices, traditions, rituals, and values, to the management of its shared wealth. A commons is best understood as a living social system of creative agents.

Economists and policymakers generally recoil at this idea because it challenges the capitalist theory of value-creation – that wealth is generated by rational individuals engaging in market transactions. The commons seen as a social system also challenges the tidy quantitative, mathematical models and mechanical, cause-and-effect mindset that economists love. If commons are treated as messy, nonlinear social activity and relationships best understood through anthropology, sociology, cultural psychology, and spiritual wisdom, it threatens the conceit of economists that their discipline is a hard science.

And yet, commons exist nearly everywhere, as if a standing rebuke to economics! They are marginalized and ignored precisely because they don't conform to the thought-categories of capitalist economics and modernity. This fact has discouraged me for a long time. So two years ago, I took it upon myself to identify dozens of projects, organizations, movements, websites, books, and literature that comprise the Commonsverse. I published descriptions of them all in The Commoner's Catalog for Changemaking to give people an idea of the enormous wealth that commoning generates. Here's a quick overview so that you can have some reference points:

Land as a commons. Decommodifying land is an important way to make land accessible and affordable for local farming, housing, and conservation. One important tool in this regard is community land trusts, which take land off the market and make it a commons in perpetuity. Land trusts help preserve the landscape, make it affordable to grow nutritious food locally, and reduce wealth inequality. Decommodifying land can happen in many other ways, too: The state or local communities can play valuable roles in providing social housing, and peer-directed projects of co-housing, housing cooperatives, or federations such as the German Mietshäuser Syndikat, can build commons-based housing.

The city as a commons. People in Barcelona, Amsterdam, Seoul, Bologna, and dozens of major and smaller cities see commoning as a promising new form of collaborative governance – and a way to reclaim cities from wealthy developers and investors. In Catalonia, a regional WiFi system of more than 40,000 nodes is managed as a commons, providing high-quality, lower-cost Internet access that corporations do. Many city governments are hosting efforts to enter into commons/public partnerships as ways to create makerspaces, systems of urban agriculture, civic information commons, and neighborhood improvement projects.

Traditional and Indigenous commons. An estimated two billion people around the world depend on commons for their everyday subsistence, through stewardship of forests, fisheries, farmland, pastures, water, and wild game. The commoning performed by traditional communities and Indigenous peoples is demonstrating healthier alternatives to industrial agriculture, and ways to protect the soil, water, and biodiversity.

Local food sovereignty in the West. There are many movements to reinvent local agriculture and food supply chains in Europe and North America. Organic local farming started this trend fifty years ago, and it is now seen in permaculture, agroecology, the Slow Food movement, and even the Slow Fish movement. Food co-operatives are a time-proven model for bringing farmers and consumers together into mutually supportive relationships – helping to lower prices, assure more stable, local food supplies, and eco-friendly agricultural practices.

Alternative local currencies. Many communities around the world have created their own regional currencies. The idea is to capture the financial value locally instead of letting it be siphoned away to major financial centers, so that it can stimulate local markets, jobs creation, and cultural identity. In western Massachusetts, where I come from, the BerkShares currency has become the most successful alternative currency in the US. Timebanking is another valuable currency innovation – a service-barter system that lets the elderly and people without much money meet their needs.

Open source software and peer production. The explosion of free and open source software over the past twenty-five years is a powerful symbol of commoning. By decommodifying code and leveraging the power of open, self-organized communities, free and open source software has built Linux, vital infrastructure for the Internet, Wikipedia, and many world-class software systems, for group deliberation, group budgeting, and cloud storage of files.

Cosmolocal production. One open source offshoot is cosmolocal production, a system that hosts the sharing of design and knowledge globally, and the physical production of things at the local level. This process is already used for motor vehicles, furniture, houses, electronics, and farm equipment. A global community of diabetics has even produced an Automatic Insulin Delivery device that is cheaper and more sophisticated than commercial medical products. One of the most robust types of cosmolocal production is for agricultural machinery, as seen in the groups Farm Hack and Open Source Ecology, which are helping small holders use world-class design plans to produce low-cost farm equipment in their local circumstances.

Creative Commons licenses and shareable content. The invention of Creative Commons licenses twenty years ago has made it possible to legally share writing, music, images, and other creative genres without payment or permission. These voluntary, free public licenses are now recognized in more than 170 legal jurisdictions of the world, enabling vast amounts of content to be shared in ways that would otherwise be considered "piracy" under copyright law.

* * *

Now, what's notable in each of these commons, is that they always draw on the peculiarities of their context. I have been astonished to discover commons dedicated to noncommercial theater; to building scientific microscopes with open-source technology; to creating online maps to aid humanitarian rescue; and to providing hospitality for refugees and migrants. In each case, people are bringing their own distinctive and irregular geographies, histories, traditions, provisioning practices, values, and intersubjectivities to the challenges of commoning. When “seen from the inside,” therefore, each commons is not only unique, it is an exercise in "world-making." This forces us to realize that the world is actually a robust "pluriverse," not a monoculture of global capitalism, neoliberal policy, and consumerism.

But….if commons are highly irregular and even unique, how then does one begin to make generalizations about them? What makes them related? We can say that a commons arises whenever a given community attempts to manage some type of shared wealth collectively, with an accent on fair access, use, and long-term sustainability. But that doesn't explain what is similar among commons with highly variable relationships and activities in many different contexts.

Silke Helfrich and I came to realize that if we are to understand commoning on its own terms, we need to adopt different heuristics and methodologies. We need to see each commons as an integrated social system that constitutes a distinct worldview. The prevailing modern worldview is simply too reductionist in claiming that commoners are rational individuals seeking to maximize their material self-interests through cooperation, instead of through market transactions.

Once Silke and I realized that commons are not resources, but living social organisms of people in relation with each other; and with the Earth and past and future generations; and that commons draw on the full emotional, ethical, spiritual, and cultural agency of people – not just their calculative rationality -- we realized that we had to abandon the grand narrative and vocabularies of standard economics. We came to realize that commoning is, in fact, a dynamic aliveness that is created and sustained through social and ecological relationships.

This is the insight that Silke and I set out to explain in Free, Fair and Alive. We wanted to answer questions like: If it's all about relationality, how exactly do diverse personalities and priorities get aligned into coherent commons? How do important things get made and care provided through cooperation, without the sole dependence on the exchange of money? If people are not to act as "consumers" or "employees" working in rigid hierarchies of power, how do peer-driven, horizontal systems of cooperation come into being and sustain themselves?

Fortunately, we were able to stand on the shoulders of Professor Elinor Ostrom and her pioneering "design principles" of successful commons. Ostrom had identified the need for clearly defined boundaries, for example, and self-created rules of governance. She discovered how commoners must be able to participate in making the rules, and they must participate in monitoring how the rules are enforced. If there are disputes, a commons must have its own low-cost, rapid system for resolving them. And commons must have independence from state authorities.

And yet, this traditional thinking about commons remains largely within the standard economic framework, as I mentioned. It doesn't give much attention to the inner lives of commoners, their cultural values and relationships, or the political economy. But a relational framing helps us see more clearly and deeply how commons actually work!

Silke and I found guidance in the work of Christopher Alexander, a dissident urban planner and architect who had developed the idea of pattern languages. Alexander had observed that certain solutions to recurrent problems appear again and again, across the divides of history and cultures. He calls these clusters of solutions patterns. They are designs and behaviors that arise from social practice, from the bottom up, and prove their value by being used and modified again and again. The pattern languages methodology helps identify the constellations of patterns that solve problems in practical and deep, even spiritual ways.

Applying this methodology, Silke and I identified several dozen patterns of commoning from the many, many commons we had witnessed. We grouped the patterns into three Spheres – Social Life, Peer Governance, and Provisioning – which can be roughly classified as the social, the institutional, and the economic. Together, these three spheres constitute what we call the “Triad of Commoning.” The Triad helps us answer, What social practices and ethical behaviors help create and maintain relationships of commoning?

The patterns we identified are not a single blueprint of best practices or fixed, universal principles. They are general solutions to recurrent problems which occur in varying circumstances across cultures and history. I can't go through the twenty-five-plus patterns we found, but let me give you a sense of the patterns.

In the Social Life of a commons, for example, one important pattern is Cultivate shared purpose and values. Without this practice, a commons falls apart. People need to share experiences and collectively reflect on their commoning if they are to remain a coherent, vital group. A related pattern is Ritualize togetherness. People have to meet with each other, share with each other, and celebrate their togetherness as a group. It's important to play together, and organize rituals, traditions, and festivities. The social life of a commons requires that people Freely contribute – to give without the expectation that they'll directly or immediately get the same value back – even though commons do deliver real benefits over time.

Peer Governance -- another part of the Triad of Commoning -- is all about seeing others as equals, and sharing the rights and duties of collective decisionmaking. With Peer Governance, you try to avoid hierarchies and centralized systems of power -- because they can be a setup for the abuse of power and accountability problems. Peer governance requires, among other things, Sharing knowledge generously. This is a crucial way to generate collective wisdom. Knowledge grows when it is shared, but this can only happen if information is accessible and freely circulating. A related pattern is Honoring transparency in a sphere of trust. Transparency can't just be mandated. It won't happen unless people trust each other – enough that they will share difficult or embarrassing information.

Finally, the third Sphere of commoning – Provisioning – is about commoners producing what they need themselves. There is no separation of production and consumption, as in the market economy. Commoners are not producing to sell in the marketplace; they are producing for themselves and allies. A basic goal of provisioning in a commons is to reintegrate one's economic needs with the rest of one’s life. Commoners aren't interested in producing a maximum amount of stuff to sell and reap higher profits. They aren't into rip-and-run exploitation of nature. They're about enhancing their personal well-being and regenerating ecosystems. One basic pattern of provisioning is Make & use together. Anyone who wants to participate and take responsibility can join. Everyone contributes according to their own capacities, talents, and needs. Co-producing is the core process of what might be called DIT -- ‘Do It Together.’

Once you begin to get into the patterns of commoning – once you begin to see how relationality is the fundamental reality of life itself -- you begin to make a shift of worldview, or what we call an ontological shift, or "OntoShift." No need to get into complicated philosophy right now. Let's just say that shifting one's worldview starts with shifts in our own inner lives and how we interpret the world. An OntoShift leaves behind the selfish individualism and transactional mindset of market culture. Instead, we train ourselves to see the world as an integrated whole driven by a dense web of relationships and mutual support.

All of this has important implications for how commoners engage with politics and state power. Commoners defend what they love, in apolitical ways – but often their dedication to their commons comes into conflict with the market/state order, which is generally eager to monetize and privatize wealth. So how can commons engage with conventional politics?

I recently heard a great quotation, attributed to Ilya Prigogine, recipient of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. He said, “When a complex system is far from equilibrium, small islands of coherence in a sea of chaos have the capacity to shift the entire system to a higher order.” I see the commons as helping people create new "islands of coherence." When enough commons are created, they become an archipelago of islands of shared purpose. They become a Commonsverse that helps people take care of their needs themselves through horizontal relationships with one another. They can express their aspirations and values, and build a prefigurative new world. They can assert their dignity in solidarity with others.

Focusing on islands of coherence doesn't mean that they will forever have to live in the shadows, unseen or neglected. It means that commoning can have experiment and flourish in a certain protected space. Commoners can have the space to develop their own vision, and to avoid co-optation and compromise.

* * *

As a philosophical paradigm and narrative framing, the commons has a lot of potential because it covers a lot of territory. It has deep grounding in biological, geophysical, and evolutionary sciences, which show the symbiotic, interdependent nature of life (Lynn Margulis, James Lovelock), the role of cooperation in evolution (E.O. Wilson, David Sloan Wilson), and the links between human culture and the more-than-human world (Robin Wall Kimmerer, Merlin Sheldrake, Wahinkpe Topa, Darcia Narvaez).

Commoning has important things to say about personal development, social psychology, cultural values and social practices. It speaks to our spiritual needs for wholeness. The political and legal history of commons helps us understand the violence and dispossession of coloniality, land grabs, genocides of Indigenous peoples, and Western development models – as well as the "domestic colonialism" imposed by investors and corporations in the West as they marketize common wealth to enrich themselves.

While it's essential to have a penetrating critique of market capitalism, state power, and modernity, it's also important that we don't get bogged down in critique alone. There must be room for creatively transcending the status quo. Here, too, the commons is helpful in asserting a fresh, forward-looking political and cultural vision. It steps outside the circle of market/state orthodoxy to declare new terms of aspiration and debate. It offers strategic priorities for protecting shared wealth. It offers proven models of creative, practical action.

I realize that my remarks probably raise more questions than they can resolve – for you and me alike! There are many complicated, important issues to be thought through, developed, and grounded in particular contexts. So perhaps it is best to consider this Green Lecture an invitation to a larger, longer conversation. May it find soil that is welcoming, may it grow deep and powerful roots, and may it produce a rich harvest!